-40%

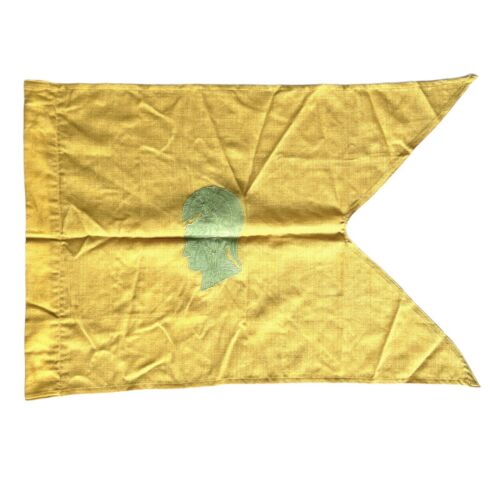

WWII M1931 Guidon: 684th AAA Machine Gun Battery (Airborne) CBI; Phila QM Depot

$ 184.8

- Description

- Size Guide

Description

WWII Phila QM Depot Guidon: 684th Antiaircraft Artillery Machine Gun Battery (Airborne)For your consideration is this museum quality M1931 US Army Guidon. The guidon was manufactured by the Philadelphia Quartermaster Depot.

684th AAA MG BTRY, (AIRBORNE)

This unit was stationed & fought in CBI (China, Burma, India) theater of opperations during WWII.

AAA were Coast Artillery during WWII, yet the use of Coast Artillery guidons were being fazed out with the CAC being abolished in 1950 with the Missile Air Defense taking over in in the late 1950s and becoming a body within the Army officially in 1967.

This guidon measures 17" x 27" and is made of wool applique on a red wool bunting. The inner lining is the OD wool/cotton lining. Its the same material that was used in the Army hancerchiefs of WWII.

A personal account of the 684th AAA MG BTRY, (AIRBORNE) while in CBI

PART I

History

The 684th AAA Battery was activated at Camp Stewart, Georgia, during September 1942. It was one of six (682nd, 683rd, 684th, 685th, 686th and 687th) activated at the same time. The officers were volunteers, young, and for the most part, unmarried. For myself, I graduated from the University of Minnesota in 1941, and had earned an ROTC Commission. After going through Anti-aircraft Artillery School at Fort Monroe, Virginia, I was assigned to the 204th AAA Regiment at Camp Hulen, Texas, where I was on December 7th.

The 204th moved to San Diego in mid-December. In mid-July 1942, I was promoted to First Lieutenant and transferred to a 40mm gun battery at Fort Bliss, Texas. From there, I attended the 40mm Bofors school at Camp Davis, North Carolina. I was then assigned to Camp Stewart, Georgia, as Battery Commander, Headquarters Battery of a 40mm Gun Battalion.

The problem was that there were three captains, each of whom had understood that he would become Battalion Executive Officer (Major). That was a situation that no Junior first lieutenant would like to be in. As soon as the call went out for volunteers for the AAA Batteries, I did.

The enlisted men came from several sources. Part from a deactivated 40mm gun battalion; part from men who had previously served as gun crews on freighters, many who had life-boat time; and the rest direct from basic training. At the time of activation, we had our shipping APO numbers, though we had no idea where we were going. The officers of the 684th were: Capt. Clyde Adkins, myself, 1st Lt. Charles Largay, 1st Lt. Charles Zerzan, and 2nd Lt. Alexander Kevorkian. There were 85 enlisted men including one First Sergeant, one Battery Clerk, three Platoon Sergeants, three Medics, one Armorer, one Supply Sergeant, one Mess Sergeant, and two Cooks. The 684th was equipped with 12 water-cooled .50 caliber machine guns, two Jeeps, and two Jeep trailers.

At Camp Stewart, we organized, drew our equipment, learned about loading C-47 troop carrier aircraft, fired on anti-aircraft and anti-mechanized ranges, took long marches (which I ducked whenever I could) trained hard, and played hard. In the evenings, many visited the Officers Club where we held "Prayer Meetings" (gathering around a piano and singing risque "barracks ballads."

I remember one practice maneuver where the 684th flew to an airfield in South Carolina and set up our anti-aircraft defense. We discovered a number of wild pigs running loose. Several were "tommy-gunned." Capt. Adkins sent a party Into town and expended some Battery funds for beer. We had an excellent Battery barbeque that evening. Breakfast the next morning was not so good. All we had to eat was cold canned salmon. The flight back to Hunter Air Field (serving Camp Stewart) was very bumpy. It was one of the few times that I almost became airsick.

After a formal inspection, we were able to get rid of one misfit. In mid-November, there was an Officer's Call. A Major, from Camp Stewart Plans and Training, told us in his thick Arkansas drawl, that we were ready. He knew where we were going, but he couldn't tell us. We wouldn't like it, but we would never forget it. How right he was!

The six separate AAA Batteries loaded up a troop train, and we set out for the West Coast. We later learned that the Officer's Club at Camp Stewart burned down the night after we left.

In New Orleans, Lt. Zerzan and Staff Sgt. Ramsey got off the train to buy cigarettes and candy for the men, and got left behind. They caught up with us in about 50 miles down the road as they were fortunate in being able to catch a fast train which overhauled us.

I was Train Mess Officer, and was able to arrange for a Thanksgiving turkey dinner with all the trimmings to be served to the men when we passed through El Paso, courtesy of Fort Bliss. On to Camp Stoneman, California, where we rechecked all of our gear, got all kinds of shots (Why don't they equip our arms with Zerk fittings?), and waited for the word from the San Francisco Port of Embarkation.

On 8 December 1942, we sailed from San Francisco on the He De France. (See Fall 1993 issue, CBIVA Sound-Off article "Troopship He De France" by Hugo Schramm; and Winter Issue letter, "More on the He De France" by Frank Hofstatter). Capt. Adkins was able to get one of our machine guns mounted on deck. This permitted our men to get more deck time than would otherwise have been permitted. In the evenings, many of us who had participated in the Camp Stewart "Prayer Meetings" continued the practice on deck.

I recall that we passed through some heavy weather between New Zealand and Australia. The He De France took green water over the bow. I escaped the sea-sickness which overtook all too many. I also recall the comfort afforded by a cruiser and destroyer which escorted us as we passed south of the Dutch East Indies. We arrived in Bombay on 15 January 1943.

The six AAA Batteries embarked on a troop train for the trip across India. It was a slow trip, and, as I recall, took over a week. We had the option of keeping the windows closed and sweltering, or opening the windows and breathing the coal smoke from the engine. Kitchen field ranges were set up In a freight car. The train stopped at meal time and we lined up and received our chow. Somewhere near Calcutta, the 686th and the 687th AAA Batteries were detached and sent to the Dacca area. The rest of us continued toward Assam.

At some point, we left the train and boarded a river boat and steamed north on the Brahmaputra River. Our next stop was at a British-operated camp where we left the boat and transferred to a narrow gauge railway for the rest of the trip to Northeastern Assam. At this camp we were warned to keep our mess kits covered as we passed through the chow line. Those who disregarded the warning were sorry. Birds (Kites?) dive-bombed and grabbed food right out of your kit.

The AAA Batteries were assigned to Forward Echelon, 10th Air Force, Headquartered at Dinjan. The staff officer for Antiaircraft Artillery (Major Meigs) made our assignments, allotted spaces at schools and rest camps, reviewed our reports, and helped us as best he could. There was no intermediate level of command. This was both a blessing and a hardship. We could demote and promote as necessary, cut individual travel orders, establish standards for wearing uniforms, set training schedules, and use our own ingenuity.

In fact, we could do everything a separate Battalion or Regiment could do. Additionally, we were seldom burdened with staff visits and inspections. On the other hand, a Captain's request for supplies and services did not carry the weight that would be given a request from a Major or Colonel. And - there was no room for officer promotion.

The 684th AAA Battery was assigned to Chabua where we joined the 706th AAA Battery in the protection of the airfield. Chabua was located at the edge of several tea plantations. Tall trees with fine leaves shaded the tea bushes beneath. Indian women (usually with a baby on her back and one in her belly) picked tea leaves and carried baskets full to multi-storied drying sheds. These sheds were open and harbored all kinds of birds and other wild life. I guess that is why we use boiling water to brew tea!

We were quartered at the Chabua Polo Grounds for a few days, and then set up a tent camp closer to the airfield while bashas were built for us. Malaria was of concern and Battery orders were that all personnel were to sleep under mosquito bars. An inspection revealed that some did not, and several gun Corporals were demoted.

The 706th had been at Chabua for some time and had undergone a Jap strafing attack. (The function of the AAA Batteries was defense against strafing.) On 23 February 1943, while we were still in the tent camp, we were bombed by a high flying aircraft - much too high for us to do any good. One officer of the 706th was killed, but aside from that, little damage was done to the field or aircraft caught on the ground. On March 23rd, shortly after midnight, we were hit by a severe rain and hailstorm. We had one tent blown down, and the 706th had three tents and five bashas blown over. Then, on April 23rd, an aircraft crashed on landing and wiped out five other parked planes. From then on, we wondered what the 23rd of each month would bring forth.

Finally, our bashas were complete and we moved in. Capt. Adkins was very concerned about the proximity of the camp of the workmen who built our bashas. It was located across a rice paddy about 25 feet from our quarters, and could be a source of malaria and theft. He contacted the Burmese who was the contractor, and who promised to have camp removed within two days. The two days came and passed, and the camp was still there. The contractor was contacted again, and he promised that the men would be gone the next day. They weren't. The contractor was again contacted and told that unless the men were gone by afternoon, they would be burned out That afternoon, they were still there, so we got some gasoline and torches and burned them out. We posted a double guard that night, but there was no trouble

The food at Chabua was supplied by the British, and was terrible. We could count on canned corned beef six meals a week with corned mutton for the seventh. About 40 percent of the eggs, when we got them, were bad. Bread was sour, and sugar was coarse, but there was plenty of tea and rice. One item I did like was canned soya flour sausages. One day we received a truck load of live ducks, and we had roast duck for dinner. We bought chickens and raised them for eggs and food, and we also bought and raised a few pigs. There was plenty of garbage for them to eat. The night after the pigs were gelded, some men had a special treat, sweetbreads.

We had quite a problem keeping the jackals away from the chickens and pigs. Another treat that we had was frog legs. There was a lot of large frogs around, and the men gigged them at night. The legs were breaded and deep fried. They tasted just like chicken. One culinary effort was an utter disaster. Mangos, sliced, had the consistency of peaches. Would not a mango pie be a treat? It was not. More garbage for the pigs. And, then came SPAM! It was good when compared to the corned beef and corned mutton that we had been eating, but weeks, months, years of Spam was too much. I very much doubt that any CBI veteran has eaten one mouthful of Spam since the war.

For a change of pace, we would occasionally eat In the Chinese restaurant In Dibrugahr. The food was pretty good, and the place appeared to be clean. We occasionally saw a movie In the Dibrugahr theater, but most of movie watching, if you could stand the odor given off by some of our garlic-eating Chinese guests, was at the Chabua Polo Grounds recreation building.

Dibrugahr was our closest town. The road to Dibrugahr had, at one time been black-topped, but the military traffic had reduced the road to a series of potholes. Vehicle springs were in high demand. Parts of Dibrugahr were neat, clean, and flowered. There was a movie theater and an Angelican Church. Other parts were filthy, and smelled to high heaven. Cow dung was plastered to walls of huts. When dried it was used as fuel.

There were many strange sights. There was a truly holy roller there. He wouldn't walk, though he had no visible affliction. He rolled down the street through cow dung and everything, singing and shouting all the time. He was accompanied by a woman who held out a begging palm. There was a woman who I saw several times whose actions made me believe that she was crazy. She went naked to the shopkeepers of the bazaar and they gave her corn and other grains. Instead of eating them, she smeared them on her face. Looked filthy. There was a beggar with a horrible looking stump of a leg always asking for "bakshish," the most frequently used word in the Indian language. Occasionally one saw a fakir. The one I saw in Dibrugahr had long kinky hair, a burlap jacket, bells, and a snakelike curved stick. His body was smeared with ashes and mud.

PART II

PX items such as razor blades, tooth paste, cigarettes, cigarette lighters, flints, and pipe tobacco, (I am a confirmed pipe smoker) were in very short supply. You did without (or shredded cigarettes) until packages from home arrived, four months later.

Mail also was slow. I ran a little experiment. I sent three letters home, one air mail, one regular mail, and one by V-mail. The air mail letter arrived first followed shortly by the regular mail. The V-mail letter came through one week later. Stamps were hard to come by. Eventually we were given Franking privileges, and stamps were no longer necessary. Because of the lousy food, the shortage supplies, the want of PX goods, and slow mail, it was of no wonder that the saying developed, "The Japs are fifth on our list."

The weather in India and Burma varied. In winter, it was not too bad. The monsoons were a different story. Hot and humid with frequent downpours. It would pour cats and dogs and within an hour there would be dust on the roads. Letter writing was done in the early morning when it was cooler, but even then you would place a piece of paper under your writing arm so that the ink would not smear. Mold developed everywhere: on shoes, belts, and Jackets; in ears, and between the toes. One of our officers got a good case of "jock itch." He felt that ultraviolet treatment might help, so on a clear day, he sun bathed on a cot. He forgot that the ultraviolet treatment would also cause sunburn. He sure did walk funny for the next few days!

As noted, the organic transportation of the 684th was two jeeps and jeep trailers. We needed more. I'm not saying that our men were a bunch of thieves, but they did have a knack for "moonlight requisitioning." There were a couple of traditional trucks around the Battery, but when British lorries started to show up at our gun positions, we put our feet down and most of the trucks were returned.

The infantry defense of Chabua was provided by a Company of the Mahindra Dal (A Regiment of the Gurkhas from the Kingdom of Nepal). Through the British liaison officers (Capt. Collard and Capt. Nicholson), we got to know the Subahdar and some of his men quite well. These fearless soldiers are very clean, industrious, and friendly when they are on your side. I still have a gift kukri given me by them. Capt. Collard was an interesting person. Only 23 years old, he had been wounded three times. He had been at Dunkerque, Tobruk, and Burma. We saw quite a bit of Capt. Collard - poker games and dinner exchanges.

We arranged for a basketball game between the 684th and the Gurkhas. The only stipulation was that the Gurkhas left their kukris at home.

While we were at Chabua, the Japanese were advancing on Fort Hertz (Putao) in Burma. It occurred to me that it was possible that the 684th might be called upon to cover an evacuation from Fort Hertz. It might be wise to look over the place. I hooked a ride on a C-47, flew over some snow covered mountains, landed, made some sketches, and returned. Fort Hertz was not much. Just a dirt strip with a few bashas. The C-47, which took off from Fort Hertz just ahead of us, must have attempted a straight climb over the mountains instead of circling to gain altitude. It crashed. It was an awesome sight seeing the wrecked plane and the oily black smoke against the crystal white snow. We circled several times, but saw no evidence of life, so we returned to Chabua. (None of the AAA Batteries were sent into Fort Hertz).

was sent to a five-day, British operated, Security Course at Gauhati. I found that there had been a mix-up on dates and I had arrived a week too early. I went up to the rest camp at Shillong to pass the time. Shillong is at 6000 feet on the Khasi Hills. The air is cool and dry as compared to the very hot and humid weather of the Brahmaputra valley. Some pine trees, neat lawns, and lots of flowers. There were horse races on Sunday, and I am quite sure that the same horses that raced on Sunday could be seen pulling wagons during the week. Shillong is also close to Cherrapunji. When the warm, moisture laden monsoon winds blow against the Khasi Hills; the air is forced upward, the moisture condenses and it rains. The annual rainfall at Cherrapunji exceeds 450 inches, making it the wettest place on earth.

The day I visited Cherrapunji was clear and I could see for miles across the Bengal delta. My stay at Shillong ended all too soon, and it was back to Gauhati.

The school had excellent instructors, and dealt with British-Indian matters (biased), as well as experiences that the British had had fighting the Japanese. Life at the school was different. We were awakened at 0745 by a bearer lifting the mosquito bar and serving a mug of hot tea. After a full breakfast at 0945 classes began. After lunch, classes ran until tea time at 1630. Dinner was served at 2000. This was a life-style foreign to American soldiers.

Now begins the alcoholic tales told to me of a lieutenant from a Highland Regiment, whom I first met at Shillong. The scene is Edinburgh. The lieutenant was on one of his evening drunks. On his way to another "spot" he was dumped into the back seat of a taxi where he passed into a drunken oblivion. Somewhere along the way, he roused enough to discern a place he knew. He said, "Here's where I get out," and did so while the taxi was going 30 miles per hour. They gathered him up and took him to a hospital where it took six weeks to piece him together again.

He was to return to his Battalion in Ireland but, as usual, he was "stewed." He wandered down to the docks and was carried aboard ship. He continued to drink as long as his supply lasted. Then it soaked through his soused head that the trip was taking longer than usual. When he sobered up enough to ask questions, he found that the ship was pulling into Cape Town, South Africa, on the way to India. He did his best to explain his way out, but no soap. A member of a cadre for India was very ill and was taken off the ship at Cape Town. The Lieutenant was put in his place to continue to India.

The Lieutenant got off the ship at Cape Town to replenish his liquor supply. He was so intent on his job that he forgot to notice where his ship was tied up. It so happened that right next to his ship was a sister ship. The Lieutenant had secured enough liquor to last him to India, and had drank enough to get him half way there. He staggered up the gangplank and into cabin 10, which was the right number, but someone else had had the audacity to move in with his baggage and had gone to bed. The Lieutenant threw the intruder and his baggage into the passageway, locked the door and went to bed.

In the morning, he discovered his mistake, sneaked back to his own ship and hid until his ship was clear of Cape Town.

The Lieutenant completed a Battle Indoctrination (Commando) course in India and earned a few days rest at Shillong. After such work a little indulgence was indicated. Well, he passed out in the club right in front of the General and his wife who made some remark about "intoxicated officers." The Lieutenant let It be known that some women he knew, talked too much; whereupon a Major escorted him outside. He went without any trouble, but later returned walking through a plate glass window on the way in.

I met the Lieutenant again at Gauhati. He came into the officers mess for breakfast with a quart of gin under one arm and a quart of lemon squash under the other. They were his breakfast. Then he got banged up a good deal when he fell down a flight of 15 stairs.

In addition to being a shipping point for food and material going to China, Chabua was an airfield where China based B-24 bombers received rear echelon maintenance, such as engine changes. When we saw a B-24 "slow-timing" an engine on the ground, we could be pretty sure that in a short time it would take off for an engine check.

Such a flight was an invitation to hook a ride. Now I loved to fly. While at Fort Monroe, Virginia, I would go over to Langty Airfield, get a ride on anything available, even an old B-18A. When in San Diego, I rode in primary trainers and in Navy SNJ's.

One day I saw a B-24 "slow-timing" an engine and started to make arrangements for a ride. The plane was parked in the middle of a huge pool of standing water. I said, "To heck with it," and went on my way. That afternoon the B-24 took off with a complement of passengers. During the flight, the pilot dropped down and "buzzed" the Brahmaputra River. There was a cable operated ferry that crossed the river. The plane hit the cable. The belly of the plane was ripped out along with four of the passengers (who were never found.)

Somehow the pilot managed to keep the plane airborne and managed to return to Chabua. Wheels were lowered by hand but there were no brakes. The plane got to the shoulder of the runway where there were small ditches which drained water from the runway. The plane hit one of the ditches and buckled nose down. Those passengers in the nose (where they were not supposed to be during a landing) had to be cut out.

The pilot took off and hid in the tea patches for several days before he turned himself in. He was later court martialed and sent back to the States. My ardor for flying cooled considerably after this incident, and I flew only on business. No more Joy-riding!

We had a casualty. Pvt M__ was cutting out the end of a 55 gallon drum with a cold chisel and was doing so without safety glasses. A piece of steel flew and put out an eye. The real strange thing about It was that during World War I, his father had been pounding on a steel drum; and had lost an eye.

In October 1943, we moved by train to Tezpur. Capt. Adkins had checked into the hospital so I was in charge of the move which went quite smoothly. Tezpur was further from the "Hump," but closer to Imphal and Kohima where the ' British were repelling a Japanese attack. The country is flat with no hills for about 40 miles in all directions, but on clear mornings we could see the snow-capped Himalayas. There was nowhere near the air activity at Tezpur as there was at Chabua.

We emplaced our guns and lived in tents until our bashas were built. My first discipline case concerned a gun crew which had painted the gun mount red, and refused to remove the paint when told to do so by the platoon commander. We now had three new noncoms who would do what they were told to do when they were told to do it.

Once the guns were emplaced, we had plenty of time for recreation. We played badminton in the evenings and cards after dark.

One evening, after a badminton game and showers, one of our men saw something on the ground under his tent. He stomped it and kicked it outside. The next morning he saw what it had been - a Banded Krait. This is one of the most poisonous snakes in India.

I played cribbage against Lt. Largay. He usually won. When we could get enough officers together, we played poker. We also read a lot of books.

One night the Red Cross came over. I got a phonograph from one of the day rooms and the men had dancing lessons. We used a blast pen for the dance floor and unfused bombs served as chairs. We also organized a few deer hunts - on elephant back. I was surprised how hairy the creatures were, and how fast they moved. We shot no game on the trip I went on, but we had a darned good time.